author Petya Koleva & editor: Kristin Oswald, the article is part of Arts Management Quarterly Issue No. 124 · September 2016 · ISSN 1610-238X

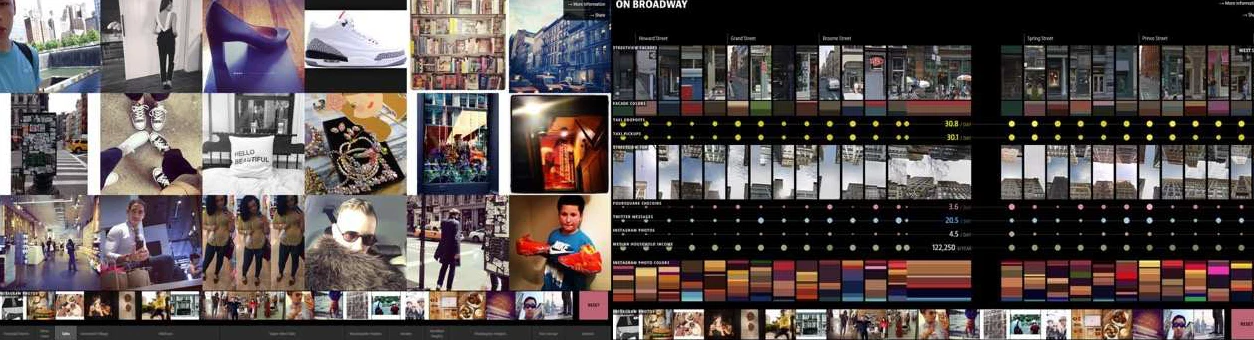

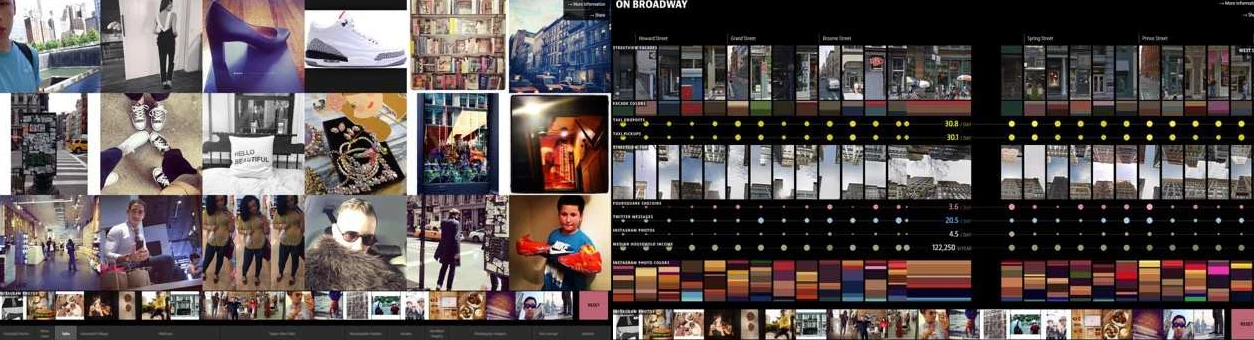

Header image: On Broadway: images shared in SOHO area (left) and printscreen from the application (right)

Designing Inclusion. Cultural Policies empowered by digital and real Audiences by Petya Koleva Petya Koleva

A) Creativity in succession

Tensions intrinsic to the “expansion of the neoliberal economy” are becoming a global factor in various aspects of life in the 21st century. Increasingly public policies ‘encourage’ citizens to engage in entrepreneurial activities including such as governing of public commons that used to be centrally managed. This does not alter the fact that the competitiveness of economies and the welfare of communities depend on clear goals. For Bulgaria, a member of the European Union (since 2007), the driving sector of the economy is information and communication technologies (ICT). In 2016 there is finally an explicit policy linking this fastest growing economic sector to the one of culture and creative industries (CCI). Yet, we ask ourselves do competitiveness and culture work together in a sustainable way? What are the particular relations of policies, the arts and the digital age that impact both the local and global communities?

„Recently the role of information technologies in how production is structured has changed and new consumption models, such as the ’sharing economy,’ are emerging. There are various understandings of sharing. Lucid illustrations of this are disruptive digital innovations we could not imagine several decades ago, which undermine the value-chain of traditionally established sectors and services by offering basic value proposition services and utilising content sharing (e.g facebook) or resource sharing (e.g. Airbnb, Europeana). These providers mediate the creation of services by engaging the users as co-investors or semi-entrepreneurs. How are they accountable to the public and which communities benefit from the gigantic profits some of these digital service providers are making?

Several decades ago, businesses aspired for building global empires, and since the networked society era (M. Castels Ed. 2005: 351) they utilise principles of horizontal integration. The emergence of peer production is attributed to the freedom to operate in a ‘commons-based production’ (e.g. Wikipedia, Wikimedia projects). Particularly in information, knowledge, and culture, commons unmodified, open commons, usable by an undefined set of users, relying on diverse and often unstructured motivational models, and based on symmetrically-applicable rules of engagement that in the public domain mean simply ''anything goes’ after a while, are the foundation” (Benkler 2011).

[Commons entail a moderately closed group of actors who rely on the commons or contribute to it, but organize themselves through relatively interdependent institutions, neither state nor market based.]

Indeed, it is one thing to share ‘images’ and ‘stories’ and another to share success, profit, or the hardships. Yet, both are communal practices and it is

the digital technologies, which offer insights into how these inter-relate. Big data analysis is a way to track key dimensions of ‘sharing’ a demonstrated in the interactive installation ‘On Broadway’ by Daniel Goddemeyer, Moritz Stefaner, Dominikus Baur, and Lev Manovich. It builds on correlating sets of images and data collected from smart devices and statistics covering the 13 miles of Broadway that span Manhattan. The result validates the fact that there is an ’invisible’ inclusion/exclusion divide to the ‘sharing’ practices.

On Broadway: images shared in SOHO area (left) and printscreen from the application (right)

[Image and data include 660,000 Instagram photos shared along Broadway during six months in 2014, Twitter posts with images, Foursquare check-ins since 2009, Google Street View images, 22 million taxi pickups and drop-offs in 2013, economic indicators from US Census Bureau (2013), and the median income of the users which is about 135,187 in the Financial District Users and 28, 323 in Haarlem.]

This analysis of big data provides insights to many commercial companies into the type of interest and engagement of thousands of people who participate in the so-called sharing economy of ideas or creativity. It also demonstrates that there are thousands of people in the digital domain who make less use of ‘public’ exchange. This unassuming visualisation of boundaries and qualities defines a sizeable diversity along one street in a dense urban area.

We may visualise the digital economy participation of Manhattans inhabitants and compare it to that of people living in agricultural areas probably ‘reading’ more into the global reality. Clearly the profiles, the content of images and messages, the intensity of interaction with other people and services would be different. Lifestyles may be influenced by individual choices. The digital shift resulting into inter and (intra) generational divides is not dependent on personal initiative exclusively.

An app developed especially to connect users and service providers within a ‘territorial’ cultural economy of ‘art miles’ sharing was Artory. "The real-time data analytics provided by user feedback gives the venues vital information about their audiences that can inform and secure investment for future projects and events,“ states Alan Williams. This is a great example of the empowering ICT use for cultural analysis and ultimately it serves the long-term interest of users as long as they are among the ones ‘participating’ in the digital sharing of culture. A Finnish colleague once indicated that there is truth in the fake marketing slogan ‘Nokia (technology) connects people and divides families’. The lure of attracting users and public indirectly may have the added value of virtual insight. Fighting for clear goals that help our societies retain cultural capital and define the public purpose of shared resources by utilising technology constitutes another type of challenge.

B) Public – private negotiations of ‘Success’

As we have illustrated above, the immersion in digital technologies brings excellent opportunities to connect like-minded individuals across a certain lifestyle and the globe. However, a policy-making which grows bottom up would quickly discover that competitiveness and the speedy emergence of horizontal networks based on inclusion and creativity are interdependent. A Global Creativity Index of 2015 by the Martin Prosperity Institute, Toronto, entitled the “3Ts” presented a new model ranking 139 nations on three pillars of development described as follows:

- Technology: Research and development investment, and patents per capita;

- Talent: Share of adults with higher education and workforce in the creative class

- Tolerance: Treatment of immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, gays and lesbians.

According to the analysts, creativity is increasingly the cornerstone of innovation and economic progress for nations across the globe. Yet behind the ‘indexes’ there are people, artists and communities interested in the values of tolerance, freedom and sustainable economies. In the advent of 2016 the research “Cultural Times” by UNESCO alerted policy makers and the artistic communities of the fact that the world is undergoing dramatic change. It will affect the way the rights of common people to access culture relate to their rights to participate in the design of culture anywhere around the world. A study commissioned by the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers affirms this powerful argument of the contribution of the cultural and creative industries to sustainable development. The pertinent point is that the industries are growing at the costs of numerous artists being underprivileged by the arts “market”.

Is a nation or city competitive because of attracting highly skilled CCI labour and affluent tourists? No, it is prosperous because it re-creates cultural industries by "avoiding elitism in new avant-garde facilities, because it tests new formats in promoting and managing the creative-based facility by empowering creative-based strategies within the local background and potential“, states Miguel Rivas in the Key Messages of the URBACT Network on Creative Clusters. Another survey on cities that are considered living labs for culture in Asia and Europe points out that those temporary cultural facilities that host arts initiatives do have a lasting impact on shaping various inclusion policies (Mangano, Sekhar 2015). Notably, the support of public authorities and private actors for most activities raising talent and transforming urban space is an essential prerequisite. A whole chapter is devoted to the analysis of the European Capitals of Culture. The forthcoming ECoC in 2019 is Matera (Italy) and its twin town of Plovdiv (Bulgaria) under the motto of ECoC 2019 `TOGETHER´.

...

What happens when the policies for culture dissolve into such thin air? Is this due to inefficiency in market terms? Many political leaders in ‘transition’ economies will tell you that one cannot maintain the cultural infrastructure of the past. Even in capitals it had been artificially inflated by state intervention and the creative class had not originated from market demand. Yet, cultural production is not a by-product of consumer interest. For example, Nokia’s history is associated with a story that reminds us that the term ‘success’ may be designed by politicians but is defined by people. The Nokia Company and the city of Helsinki tried to reach an agreement that allowed the city to acquire the empty valuable lot of the Kaapelitehdas (or Cable Factory) from Nokia’s industrial heritage to repurpose for public benefit. In the interim period of the proceedings, artists and companies were renting the unused, decaying infrastructure. Faced with the restructuring plan, they founded the Pro Kaapeli association to create a parallel plan [to the one of the city committee] to save the building and the activities. ‘Pro Kaapeli was featured in the leading national newspapers and national TV and managed to dissolve deeply rooted prejudices against house squatters and artists who were often considered as shady’, claims the official website.  The

The

The facade of the Cable Factory today (left, © Jean-Pierre Dalbéra/ flickr) and visitors of the Finncon 2009 (right, © kallu/ flickr)

Pro Kaapeli also pointed out deficiencies in the planning of the area and even got the media involved. The Cable Factory was to remain in its original form. This was ground-breaking. A new agreement was made with Nokia, the city council decided to protect the Cable Factory and its milieu and an estate company was founded. Almost all tenants were allowed to stay.

Cable Factory today is a flagship enterprise in the cultural sector in Europe with three museums, thirteen galleries, dance theatres, and art schools, along with facilities for visual artists, bands, and companies. It hosts concerts, exhibitions, festivals and fairs. The reconstruction project of the public estate company „Kiinteistö Оу Kaapelitalo“ started in 1991 and returned its investments in fewer years than expected (Koleva 2013). Its turnover in 2005 was 3,5 million euros and over 5 million euro in 2012. Yet, the viability of this investment project was being questioned every time newly elected city officials came to power. The former Economic Director of „Kiinteistö Оу Kaapelitalo“, Mr. Nikula Stuba explained this with the banal fact that public officials are among those who assume the right to define ‘public interest’ (Sorbello, Weitzel 2008).

All around the globe corporate interests invested in mega construction projects have been documented to induce gentrification, as Harvey Morris stated in the New York Times and cause disruption in community life. Artists are a driving force to transform a ‘ghetto’ area/ infrastructure into a ‘space’ of creative manifestation; inevitably the ‘art hype’ attracts public. Typically younger audiences follow the vibe of change which prompts increased popularity and the rise of property prices. Eventually, an economic restructuring plan leads to the displacement of artists and local residents as well as their small businesses. In a case study from Barcelona, the redevelopment plan of a former factory involved purposefully attracting artists to gentrify the area (Casellas, Dot-Jutgla, Pallares-Barbera, 2012, 104–114). The efforts of artists and local community put up to stop this plan, were not fully successful. In Sofia, the plan to transform a former industrial zone of the capital into an arts quarter has manifested curator-mediated attempts to attract artists towards a private property and prompt the municipality to consider a strategic investment in the area. For the moment, the bad conditions of the infrastructure have frozen the plan. This example is symptomatic of an essential question: Who takes decisions on behalf of the public when they involve public investment in culture? In Bulgaria’s particular post-transitional economy the cultural zoning plan might have meant investing public money to acquire sites and buildings that had been privatised in often not transparent ‘post-socialist state’ deals. [Based on personal interviews with independent artists, cultural managers and Sofia Development Association in December 2015. See ‘Индустриалната зона на Сточна гара става квартал на артистите’ 28.02.2014, 24 часа онлайн.]

|

The fall of 2016 will mark a precedent in Sofia’s recent history that got me involved into the design of a participatory policy process since the initial draft of this article this spring. For the first time, the city authorities are backing the dialogue with non-state actors towards a common goal, boosting the potential of Sofia’s growing independent contemporary arts scene. ‘Shared Vision’ is the brand name for a cultural strategy that fosters the development of Dance, Literature, Music, Visual Arts and Theatre. Immediate results are expected to manifest by 2019, the year Bulgaria will take over the presidency of the Council of the EU. By then two purposefully refurbished municipal sites should open as centres in partnership with the free contemporary arts scene. By 2023 the support for the free initiative of organisations, artists, formal and informal associations should transform Sofia into an attractive place for co-creation, public interaction and professional development in the arts. The future, we hope, will be more certain.

|

|

C) ‘Success’ designed by creative ecosystems

Throughout Europe and globally, cultural centres used to be civil initiatives that are undergoing serious challenges. Their business modelling should evolve with the attempt to reconnect to the public. Trans Europe Halles’ independent cultural centres determine three key similarities of all success stories shared from the network members (which includes „Kiinteistö Оу Kaapelitalo“). Sustainable cultural businesses tend to:

1. Mix and merge new and traditional types of services by offering diverse arts forms as well as providing recreation type services;

2. Rent out spaces to other organisations;

3. Engage volunteers and freelancers in organising multiple events per year.

The core indicators of success suggest that “cultural operators and artists do much more ‘business’ than we think… [They] create a lot of value, but not always get paid for it…” (Schiuma, Bogen, Lerro, 2015). It also highlights the importance of improving the business models to survive in differently structured competition/ cooperation models among providers. The hybrid model is emerging in Bulgaria, in Ukraine, in Finland and in Germany, in fact in very distant yet very similar locations. Cultural organisations should not be the ‘dupes’ of neoliberalism, slaving for the ‘public good’. That capital is not only difficult to measure (symbolic value) but also hard to accrue because skilled managers leave this low-paying sector. Performance measurement is (still) rarely implemented in the public sector in Europe. One can hardly expect the effort to grow, budget cuts are easier when there are few evidence-based cultural policy incentives. Yet, this may change if the digital shift enables the measurement of the impact of externalities as it is meant to do. This will empower the cooperation of networked entrepreneurs too. Behind this shift there needs to be

a political will.

Despite the philanthropic drive of of individuals, certain public goods such as affordable and accessible arts derive from the right of people to participate in the ‘shared’ economy of values. Among them is the right to designing state intervention. In the early twenty-first century cultural organisations are seen as the major contributors to social welfare and producers of intangible cultural capital. There have always been explicit as well as implicit policies that shape or undermine their success (Koleva, Cherrington, 2010). "In 2015, triggered by terrorist attacks in Paris, Italy’s Prime Minister Matteo Renzi has pledged 1 billion euros to spend equally on culture and security. The Bardo Museum in Tunis, site of the March attacks, announced a cultural partnership with the Museo di Arte Orientale in Turin, Italy, in an effort to contribute to peace and stability in the region.“, stated Create Equity in December 2015.

Some policies regard the governance of public space, others the distribution of wealth for public purposes. There is an intricate interplay in which public ownership and not-for-profit business correlate, but that is not necessarily the only option. For example, more and more privately owned for-profit creative businesses run co-working spaces. Yet, for micro non-profit arts organisations it is uncommon to manage a cultural infrastructure jointly with a legal for-profit entity. The great success of ‘The Cable Factory’ besides its economic achievement as a self-sustained ‘independent’ art space is its innovative business model. The estate company owns the infrastructure and this allows it to plan its future years ahead. That provides a micro ‘systemic’ context, uniquely apart from the position of many singular entities dependent on ever-changing budget lines for cultural support.

[An efficient governing structure mirrors the ecosystem’s participatory principle. The Board of Cable Factory has eight members: two from main political parties, two from the city departments, thee tenants and an outsider as a chairman. With special thanks to Mr Nikula Stuba, who returned comments on this case study in November 2015 even as he is presently holding a new position, Cultural Director of the City of Helsinki Cultural Office.]

Arts and Culture coexist on democratic terms in a shared ‘space’ where they pay rental charge adjusted to their capacity to produce a turnover. The range translates into ‘symbolic’ rents for the art studios and cultural micro enterprises to ‘large’ costs for CCI companies such as multimedia content producers. It allows a sustainable ecosystem to be built along the spectrum of the ‘knowledge-intensive” cultural creative industries (CCI).

[Typically, the hours invested in harvesting talent and in creating a new art work are not commensurable with the profit to be made in the first ‘public’ presentation. An original piece of music, a drawing, a choreography, or a script etc. go into the ‘product’ that may attract the multiple viewers, listeners or live audiences. It is the agents, not the artists, who typically reap the economic benefit.] Such a ‘shared risks’ governance model suits the 21st century well because the open innovation aspect of the creative cohabitation is seamlessly redistributed into ‘sustaining’ talents. This allows a wide range of high quality products and services that may be free of charge or pricey to originate under one roof.

The hybrid for profit/not for profit participant-based development model has a multiplier effect. Kiinteistö Oy Kaapelitalo has championed a similar transformation in a former electrical power plant. It is now also administering the premises in Suvilahti. “The policy is that the area is being held as a cultural cluster an developed piece by piece, little by little. There has not been and will not be an opening ceremony for Suvilahti – the area is in a constant swirl of change and development” (Kuusimäki 2015). This quote comes from a students’ summer school that was researching

New Urban Hybrids as a global trend in 2015. There are plenty of reasons why inclusive policies should consider cultural infrastructure and its

impact on arts management, and, to boost it, integrate digital access to policy participation and impact assessment.

D) Arts Managers- demand and participation

Globally, creators and owners are disconnected early on through the market mechanisms and so are the people who access digital offers or have the means or knowledge to participate in policy creation. The Viva Cultura Communitaria policy of Brazil is famous for the fact it started out of a civil society movement of a new kind. Arts and culture activists pledged to draw attention towards policy to support the live arts and cultural forms of manifestation in communities across Latin American countries. After a decade, the international participatory process, involving gatherings, manifestations and elaboration of proposals by the movement has managed to channel a policy. In 2014 Brazil passed a bill dedicating 0.1% of the federal budget to live culture. For most post-socialist countries in Europe the entire budget for culture is about this percent (including the arts, heritage protection, visual arts, and libraries). Another significant aspect of this policy is that it is ‘fostered’ rather than ‘governed’ by the state. There are several layers of decentralization structuring priorities and the distribution of funds. These lead to a recognition of initiatives of ‘any entity that develops or articulates cultural activities in the community’. With a plan to expand the network of pontos de cultura to 50 000 by 2020, the policy has introduced a system where proposals can even be submitted per video, so that no language or literacy discrimination may impede community cultural manifestation.7 [Special thanks to Ms Marcia Rollenberg, Secreatary of Culture, Ministry of Culture of Brazil

who presented this and discussed details in 2015.] Technology is thus used to mediate inclusive cultural policy in a way that supports cultural activities originating locally even outside urban areas.

In 2016, the European Commission launched a special action call in the frame of the Horizon 2020 programme to ‘boost synergies between artists, creative people and technologists’. This is step in the right direction that will encourage more artists and CCI managers to consider hybrid partnerships. The challenge of the future is to step into participatory processes of research and management before the processes of creation driven by already predetermined visions of business and profit generated by ‘market-ready’ prototypes.

With this final example our discussion comes to rest for a moment. There are obviously powerful ways in which to innovate cultural services and products not least of all by engaging people in active policy making and creative economy modelling. I would like to thank Ms Mary McBride, Chair of the graduate Design Management and Arts & Cultural Management programs at Pratt Institute for urging me to put some of these points in writing. The informal global professional networking mode in which we operate today, brought us together in the summer of 2015 for an informal discussion. We spoke of the growing recognition of new skills needed to manage transformation and benefit from new processes of engagement undergo in various arts/cultural projects around the globe. The know-how of arts managers moves towards creating an insider experience with experimental forms of policymaking and collaboration with stakeholders, not only authorities and citizens but also other arts organizations, ICT partners, virtual communities, various researchers and the new digital data analysists etc. This article has not touched on the important hybrid models of management of artist’s rights, the relation of virtual and real performance venues/markets or on arts management based on co-financing by user-demand that other colleagues have begun to explore. I hope the four sections have triggered some arts managers to recognize and work together in concerted effort for policies that also structure professional development programmes at international level and

across the profit/ non profit, virtual/ live realm, large/ small organisations divide.

Recommended Literature

• Benkler, Y. (2009). Peer Production and Cooperation. In: Bauer, J.M., Latzer, M. (eds.), Handbook on the Economics of the Internet. Cheltenham and Northampton, Edward Elgar.

• Benkler, Y. (2011). Between Spanish Huertas and the Open Road: A Tale of Two Commons? Presentation during the Convening Cultural Commons Conference at New York University, September 23–24 2011.

• Casellas, A., Dot-Jutgla, E.. Pallares-Barbera, M. (2012). Artists, Cultural Gentrification and Public Policy. Urbani Izziv Urban Challenge, 23(1), pp. 104–114.

• Castells, Manuel and Cardoso, Gustavo, eds., The Network Society: From Knowledge to Policy. . Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins Center for

Transatlantic Relations, 2005

• Koleva P., Cherrington R. (2010). Implicit Cultural Policy – the Role of Social Clubs in Communities – Intercultural Training Module for culture operators. Tagete, Pontedera.

• Koleva, P. (2013). Innovation projects as a strategic development factor for cultural organisations. Sofia, Orgon/ Intercultura Consult ®, 01/2013.

• Kuusimäki A. (2015). Urban transformation through culture. Regenerating the old electricity production facility of Suvilahti in Helsinki. In: Lilius J. (Ed.) New Urban Hybrids Re-setting Borders, Combining Scales, Aalto University publication series CROSSOVER 1/2015.

• Mangano, S., Sekhar., A. (2015). Cities: Living Labs for Culture? Case studies from Asia and Europe. Singapore, Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF).

• Schiuma, G., Bogen P., Lerro A. (2015). Creative Business models: Insights into the Business Models of Cultural Centers in Trans Europe Halles’.

• Sorbello, M., Weitzel, A. (eds.) (2008). Cairoscape – Images, Imagination and Imaginary

of a Contemporary Mega City. http://cairoscape.org